I've been thinking about this analogy of a door to define what art is (door as functional object, door as embellished object, and door as threshold intervention). It's a common question but I've always found the range of possible answers troublesome and ambiguous. How I got to thinking about "what art is" comes from my current frustration with my path in sculpture.

I have lost my reason (did I ever have a plausible reason?) for making in this context. I have not lost my reason for making in landscape architecture. I will get to that later.

I simply do not know why to do art and why I should create art.

A part of this frustration stems from my question as to how art contributes to society. It is human nature to attach a value to something, to appraise it for its worth: using time well, spending well, eating well, etc. I am not going to argue against this. I find that value -- that assessment of our environment -- forms our identity of self, and when summed as a whole, forms our identity of society. Going by this logic, every individual's identity -- who they are, what they do -- contributes to a culture, which when shared by others, forms a society. But, then, what of this idea of those artists who create art because they enjoy doing so? They create because they enjoy it and thus, that becomes their identity because it is something that they are or that they do. Does this directly translate as a contribution to society? Does it hold tangible, perhaps material, value?

Somehow, creating a sense of enjoyment for themselves and since some people think alike, for others as well, does not suit me. Perhaps being thus far ingrained in landscape architecture, which, as a design profession attempts to create usable, "practical" spaces in a larger environment (usually far larger in scale than for sculpture)*, I have grown accustomed to objects and spaces being created for an applicable function. There must be a benefit beyond simple desires of pleasure, which I liken to simple desires or levels of thought. I think the purposes of creating art that defines our surroundings should have more thought invested in their creation. I do not mean its fabrication, I mean it's concept. Therefore, I think that art created because one enjoys creating it is not art. It still is something, but I do not know what the term would be. One could use "low art" and its counterpart, "high art", but I think it is too patronizing to separate the two as two distinct and unrelated entities. It would be better to think that this "not-art" is a lesser developed plane of thought; but that it is as developed as possible, in that environment, for that person.

Several weeks ago I was looking for the writings of three levels of thought. It was in fact three levels of experience. I first came across it while writing a theory paper. My question was: How does luminance define and radiance transcend depth perception in relation to abandoned unnoticed objects in a landscape? I can't say that I answered that question to any sufficiency, but, while reading about archetypal phenomena I discovered Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his phenomenological method. Goethe's method is typically used for scientific purposes, but I re-purposed it for my own needs. I suggested using Goethe's highest level of experience as a means to quantify the "highest level of awareness of active objects interacting with passive objects defined only by the luminous but transcended by the radiant."

Perhaps if I applied Goethe's method to the level of experience that "non-art" would most likely entail, I can begin to understand that synthesis of art is dependent on our levels of experience. A level of experience is not knowledge of technical methods. It is the experience of awareness -- much akin to the awareness of the world from when we mature from a child to an adult. Goethe's levels of experience, which he termed each as a type of phenomena, are as follows:

- Empirical phenomena are observations that an observer makes of the world around him

- Scientific phenomena concerns a higher awareness that questions the conditions that those observations make in the world

- Most would be content with this knowledge, but, knowing the insatiable curiosity of man, Goethe created a final term for those yearning in achieving the highest level of experience possible: archetypal phenomena. In essence, it does not question the conditions, it questions the observation itself.

So I am thinking that this "non-art" is a developed observation that an observer makes of the world around him. It is certainly not an... amateur? thought. But neither is it complete. I find this level much akin to the many artist statements that describe their interests in "exploring positive and negative space." I've always been troubled with such an artistic assessment because, in terms of sculpture, exploring positive and negative space is in the nature of what you are doing by carving, casting or fabricating objects together. Admittedly, I may have used such language in my college years to describe elements of my work. But I think my thinking has matured after I tried to understand what my Senior Project adviser, Ray DiCapua, once said to me when I described the thinking behind a work. He said what I described was what the work is doing, but he said I didn't explain what the work is about.

I was recently reading in Sculpture magazine about a dismissive remark towards "process work." I am interested in this perception of process work because I created a series of works based on a process for my Senior Project. Is this only one critic's dismissal or is this a wider trend? How is this important? I do not mean to suggest that I temper my work with herd behavior, but I am interested in what others are thinking about in their work. By comparing and contrasting their thinking to mine I can question more about my own work.

The works I created for the Senior Project were a series titled Order, Efficiency and Resistance. It was a process-based work because it was much akin to a one-man manufacturing line. The process for each sculpture was the same. I attempted to be both efficient in their fabrication and in the manner of how the material resisted against itself and to the others that it was attached to.

I cut 1/4" flat stock down to size and welded a skeleton frame together. I took sheet metal and hand brushed with a steel brush. I clamped the sheets on the edges and bent them. During this process I was met with resistance in making. But it was not until I riveted the sheets together that I felt a presence of resistance, a stored energy, of the sheet metal straining against itself and others. The resulting concave curve was created by that strain and I had little control over its eventual shape.

If I were to refer to the three levels of experience, I would identify this work as empirical. It was one possible interpretation of gravity and the material properties of steel at a basic level of understanding. I understood the ductile properties of metal. Yet, I did not understand the possibilities. I did not, for example, consider how the material rests against itself; as was the case with what DeWitt Godfrey explored. I think that the title, Order, Efficiency, and Resistance described what the work is doing, but not what it is about. I've misplaced my typed Senior Project statement, but this is a sketchbook entry from April 7, 2006:

Senior Project Statement

- Order }

- Efficiency } Conceptual meaning and material meaning

- Resistance }With order, one is able to establish a system. With a system, efficiency is created and managed. With efficiency, resistance is created and managed. A more efficient system is met with less resistance provided that systematic order is kept. Does a more efficient system encounter less resistance?

If a mass production (most efficient) frame of mind is kept, one loses the individual connection to the work. Therefore, it is not my intention to have a highly efficient, ordered system. While this system of production is important to utilize to explore the concepts of order, efficiency and resistance -- the investigation of the material properties of steel along with the fabrication methods and the system of order ordered system is the concept behind my work.

What the metal allows me to do within these parameters is the concept behind my work.

Without forcing -- allowing the metal to breathe.

Rivets vs welds --> Welds are forced, rivets allow breatheability and strength with compromising too much flexibility.

I remember being disappointed with the work at the time, but I could not identify why. I did some thinking while on the Fulbright, but it wasn't until January 2009 I finally had a breakthrough. Through a twist of fortune, I created an independent study on the basis of Robert Irwin's Four Categories of Sculpture (written in his 1985 essay, Being and Circumstance):

I designed a response to each of Irwin's typologies in the context of a landscape. This landscape was the Roger Williams National Memorial in Providence, Rhode Island. I determined to site each sculpture appropriately and the research reflects this in the "higher" types; namely site specific and site determined.

1. Site dominant. This work embodies the classical tenets of permanence, transcendent and historical content, meaning, purpose; the art-object either rises out of, or is the occasion for, its “ordinary” circumstances – monuments, historical figures, murals, etc. These “works of art” are recognized, understood, and evaluated by referencing their content, purpose, placement, familiar form, materials, techniques, skills, etc. A Henry Moore would be example of site dominant art.

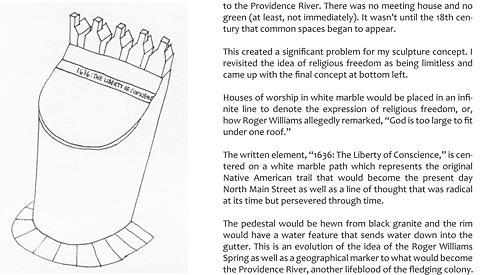

I proposed a water-fountain-sized monument to religious freedom at a location that culturally expected to have something in its center. I understood the idea of site dominant in that the work could be in a park, in a gallery, or in a bathroom. It did not matter where it was because the work took no bearing of its environment. The bronze I cast for the Fulbright was site dominant because it did not consider site context or environment.

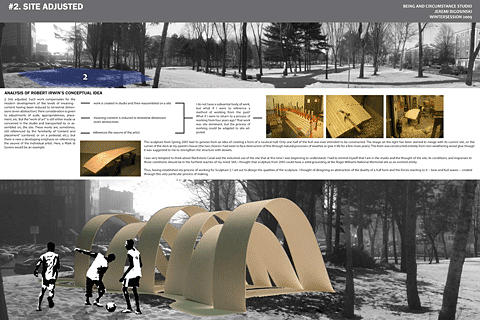

2. Site adjusted. Such work compensates for the modern development of the levels of meaning content having been reduced to terrestrial dimensions (even abstraction). Here consideration is given to adjustments of scale, appropriateness, placement, etc. But the “work of art” is still either made or conceived in the studio and transported to, or assembled on, the site. These works are, sometimes, still referenced by the familiarity of “content and placement” (centered, or on a pedestal, etc.), but there is now a developing emphasis on referencing the oeuvre of the individual artist. Here, a Mark di Suvero would be an example.

I had the most difficulty with site adjusted. I eventually went back to a sculpture I created in 2005 to synthesize an idea for this category. I did not have (still do not have) a substantial body of work so I chose this sculpture as it is reflective of my process of working. I envisioned this sculpture being constructed much akin to the work I created in 2005, but it would be adjusted when reassembled on the site. My Senior Project could be considered site adjusted as well, if only because it does not "fit" into the classical tenets of site dominant in that it does not rise out of "ordinary" circumstances nor have a familiar reference.

I had the most difficulty with site adjusted. I eventually went back to a sculpture I created in 2005 to synthesize an idea for this category. I did not have (still do not have) a substantial body of work so I chose this sculpture as it is reflective of my process of working. I envisioned this sculpture being constructed much akin to the work I created in 2005, but it would be adjusted when reassembled on the site. My Senior Project could be considered site adjusted as well, if only because it does not "fit" into the classical tenets of site dominant in that it does not rise out of "ordinary" circumstances nor have a familiar reference.

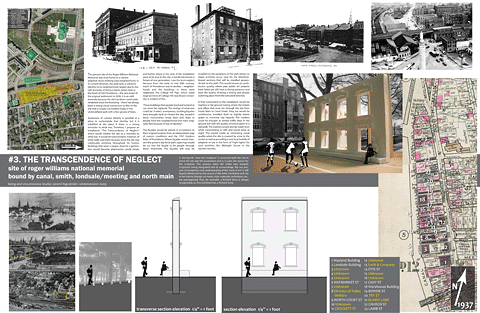

3. Site Specific. Here the “sculpture” is conceived with the site in mind; the site sets the parameters and is, in part, the reason for the sculpture. This process takes the initial step towards sculpture’s being integrated into its surroundings. But our process of recognition and understanding of the “work of art” is still keyed (referenced) to the oeuvre of the artist. Familiarity with his or her history, lineage, art intent, style, materials, techniques, etc., are presupposed; thus, for example, a Richard Serra is always recognizable as, first and foremost, a Richard Serra.

The third response traced the streets and buildings that once were on the site, before the area was cleared for the Roger Williams National Memorial. Lost records prompted me to consider an anonymous white facade to represent a ghostly encouragement of adaptive reuse (as was the nature of the site prior to the Memorial), especially in the evening as a renewed gathering place. During the ASP en-plein-air in Arpil 2007, I created an earthwork that was site specific:

Excavated from the 14th to 17th at the Center for Polish Sculpture at Oronsko, Poland, the work was created by a similar repetitive process that I used for that wood sculpture from 2005. I was very particular to displacing a cube of earth in the most exact manner in which it was created. Here is a paragraph of what I had intended with this earthwork:

That which is above the surface of the ground is full of life -- it is our inhabited environment. That which is below is not thought to be the same -- lifeless, deathly and colorless. The dimensions of the earthwork approximate that of a casket. It attempts to excavate the exact dimensions of a casket -- a rectangular box whose resident is lifeless soil. But the seeping of water at the bottom of the casket questions that lifelessness. The surface beneath is in fact a mirror of what is above, but its representation is quite different due to the near solid nature of the ground versus the near transparent nature of the above-ground.

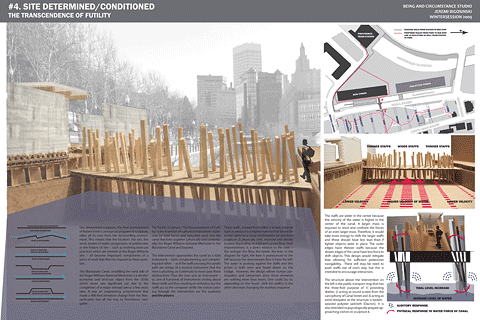

4. Site conditioned/determined. Here the sculptural response draws all of its cue (reasons for being) from its surroundings. this requires the process to begin with an intimate, hands-on reading of the site. This means sitting, watching, and walking through the site, the surrounding areas (where you will enter from and exit to), the city at large or the countryside. Here there are numerous things to consider; what is the site's relation to applied and implied schemes of organization and systems of order, relation, architecture, uses, distances, sense of scale? For example, are we dealing with New York verticals or big sky Montana? What kinds of natural events affect the site -- snow, wind, sun angles, sunrise, water, etc.? What is the physical and people density? the sound and visual density (quiet, next-to-quiet, or busy)? What are the qualities of surface, sound, movement, light, etc.? What are the qualities of detail, levels of finish, craft? What are the histories of prior and current uses, present desires, etc.? A quiet distillation of all of this -- while directly experiencing the site -- determines all the facets of the "sculptural response": aesthetic sensibility, levels and kinds of physicality, gesture, dimensions, materials, kind and level of finish, details, etc.; whether the response should be monumental or ephemeral, aggressive or gentle, useful or useless, sculptural, architectural, or simply the planting of a tree, or maybe even doing nothing at all.

The fourth sculpture, "The Transcendence of Futility" is an insertion of a physical instrument of process [of tidal forces and industrial uses] into the canal that links together [physically and contextually] the Roger Williams National Memorial to the Blackstone canal and beyond. The intervention approaches the canal as a tidal instrument that the river is plucking as it attempts to move past these obstructions. Thus the river acts as an instrument -- or, one of hundreds of instruments circling about these staffs and thus creating an orchestra, but the staffs act as the composer[s] while the visitors passing through the intervention are the audience and the players.

Applying Goethe's three levels of experience to Irwin's conceptual definitions of sculpture suggests that the first two, site dominant and site adjusted are empirical phenomena. Site specific would be subject to scientific phenomena and archetypal phenomena would be explored in site conditioned/determined. Site adjusted could be scientific phenomena -- it's on the threshold between empirical and scientific -- but the example that Irwin suggests, a Di Suvero, reminds me of a retrospective in the December 2008 issue of Sculpture Magazine on John Henry. In that interview, I came across a question that was asked to Henry about how he chose the color red for his sculpture. He replied that he uses color as a "contrast element." That's all. A sculptor who has work on five continents and has built over 2,000 'architectonic structures', many with bold reds, blues and weathered browns, uses color only as a "contrast element." That is completely unacceptable to me, unless I labeled Henry's "art" as "non-art." It only makes observations of the world around it -- yes, a red would contrast with the blue of the sky, but, why can't he question the purpose of contrasting? If that's important for the sculpture's context, why [just] with color?

Victor Cassidy: What's the role of color in your work?

John Henry: I've never really been concerned with color that much. Since I quit painting, I've never been a colorist. I use color as a contrast element, and I change the color on pieces. If I put a piece in the woods, it can't be black. If it goes by white sand, I might change it back to black. Color is something to allow people to see the piece. It relates to the eye. The shape relates -- it's a different brain function. The formal elements of a piece don't have too much to do with color. They have to do with light and the way the light articulates shape. Color reflects light, it's just another tool. [Sculpture 27.10, 54]

I think several things he says about his work are not true to his work, and I still question his use of color at all if he says that color is of little concern to him. John Henry is a contemporary of Mark Di Suvero, both in age and work, but I do not need to tell you that the work is site adjusted because their work is similar. Henry says so himself in the quote above: "If it goes by white sand, I might change it back to black." It means that after leaving the studio, his work may be adjusted on the site -- siting, color, etc.

Are the works that I "created" most recently "is-art"?

[note]I think it's time to close this post (it's clocking nearly 3,100 words) and continue on to the next. I still want to write about some comparative studies, define which works are (and how they are) "non-art" or "is-art" and come to some kind of conclusion...[/note]

How does luminance define and radiance transcend depth perception in relation to abandoned unnoticed objects in a landscape?